Icons of Mary

We invite you to share with us your prayerful reflection on The Sunday Gospel readings with Bishop David Walker, Fr John Frauenfelder and Virginia Ryan These Lectio Reflections provide the framework to develop our faith life. Our faith is in Jesus who comes to us as the human face of God. Faith life is human life lived in a deeply personal and intimate relationship with Jesus. Jesus is our friend and lover, the most significant point of reference in our life. We need to lead our life conscientiously and intentionally so that all that we do is done within the context of our love relationship with Jesus. Lectio Divina is one of the ways we can develop this.

Mark 1:1-8

The Proclamation of John the Baptist 1 The beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ. 2 As it is written in the prophet Isaiah, “See, I am sending my messenger ahead of you, who will prepare your way, 3 the voice of one crying out in the wilderness: ‘Prepare the way of the Lord; make his paths straight,’ ” 4 so John the baptizer appeared[e] in the wilderness, proclaiming a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins. 5 And the whole Judean region and all the people of Jerusalem were going out to him and were baptized by him in the River Jordan, confessing their sins. 6 Now John was clothed with camel’s hair, with a leather belt around his waist, and he ate locusts and wild honey. 7 He proclaimed, “The one who is more powerful than I is coming after me; I am not worthy to stoop down and untie the strap of his sandals. 8 I have baptized you with[f] water, but he will baptize you with the Holy Spirit.”

Lectio Reflection – Second Sunday of Advent – Mark 1:1-8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o9SNPXSdlwc

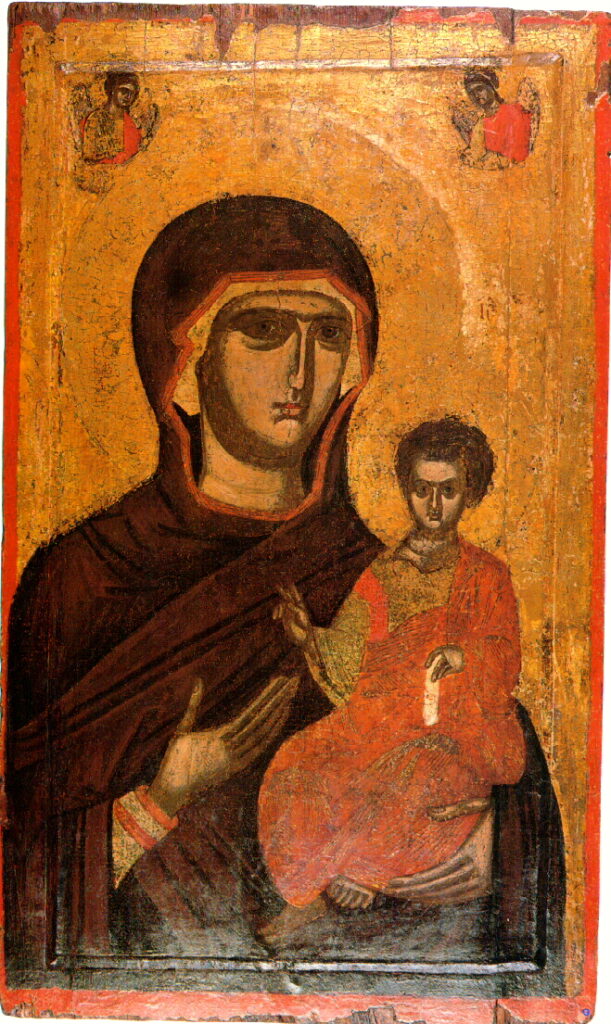

The Mother of God Hodegetria

This icon was thought to have come from St. Luke, who began the painting which was then finished miraculously. Tradition says it was obtained by the Empress Eudoxia in the Holy Land in the fifth century and brought to “ton Hodegon” monastery. The title could come from the monastery but could also come from the understanding of Mary as ” guide “.

In the most characteristic form of the icon, the virgin and the child are shown frontally. She carries the child on her left arm, although it is more like the child being enthroned there, as if there was no weight on the arm at all. It is a solemn scene: Mary is the Theotokos, the God-bearer, and Jesus is the Lord, Emmanuel. There is no tenderness between mother and child; this is not an icon in which their human physical relationship is shown. It is the Word incarnate who is revealed, and the one through whom he became incarnate.

The child is really depicted in an adult way, clothed as a wise man, bearing the scroll, the sign of the Word incarnate, and blessing with his right hand. He is an imperious figure. Often in the halo the words “o wn” are written, reminding one that he is “the one who is” of Exodus 3:14. It is the divine power of the child that shines through in this icon, rather than his humanity.

Mary too is very stylized in the icon. Not the tender mother, but the dignified bearer of the divine child. There is an aloofness in her presentation, a definite avoidance of any emotional elements. Her right hands seem to point to the child, a gesture that is accentuated by the long, slender fingers. It is the child which dominates the icon. The virgin does not look at the child, but out to the viewer or over the head of the child. Some see Mary here as the Church, presenting the divine Jesus to the world.

Mother of God, Our Lady of Vladimir

This is an example of an icon of loving kindness, which stresses the mutual gestures of tenderness between the mother and the child. Whereas the Hodigitra icons emphasized the divinity of Jesus, these icons focus on the human dimensions of motherhood and incarnation. This type of icon is more Russian than Byzantine, though the original icon of Our Lady of Vladimir came from Constantinople to Kiev in the twelfth century and was brought to Vladimir between 1156 and 1167. It was removed to Moscow in 1395, where it has played an important role in the life of the people.

The two figures blend together in the icon, forming a unity of tender love. Mary’s head is turned slightly to the child, and her cheek is pressed against his. There is a sadness on Mary’s face which is related to the suffering that her son will undergo. The icon is often associated with the presentation of Jesus in the Temple, where Mary learns of the suffering that he will endure. She grieves deeply for her Son’s coming passion. The contrast between the gentleness of the icon and the horror of the passion gives an important dimension to the icon. Mary does not look at the child, but rather faces the spectator with a solemn, restrained emotion. The eyes of the Virgin are expressive. Once again, it is the child who becomes the focus.

The child is clothed in golden attire, but is not depicted in the aloof, imperial way of the Hodigitria icon. The cheek pressed to his mother’s, the hand around her neck, the bottom of the left foot showing beneath his garment, all point to the human dimension of his incarnation. However, the child is richly attired and is more than a suckling, which reminds us that this child of such tenderness is really the Lord, Emmanuel., presenting the divine Jesus to the world.